Percy, Ward & Williams Family Paintings Percy, Ward & Williams Family Paintings  |

Percy, Ward & Williams Family Paintings Percy, Ward & Williams Family Paintings  |

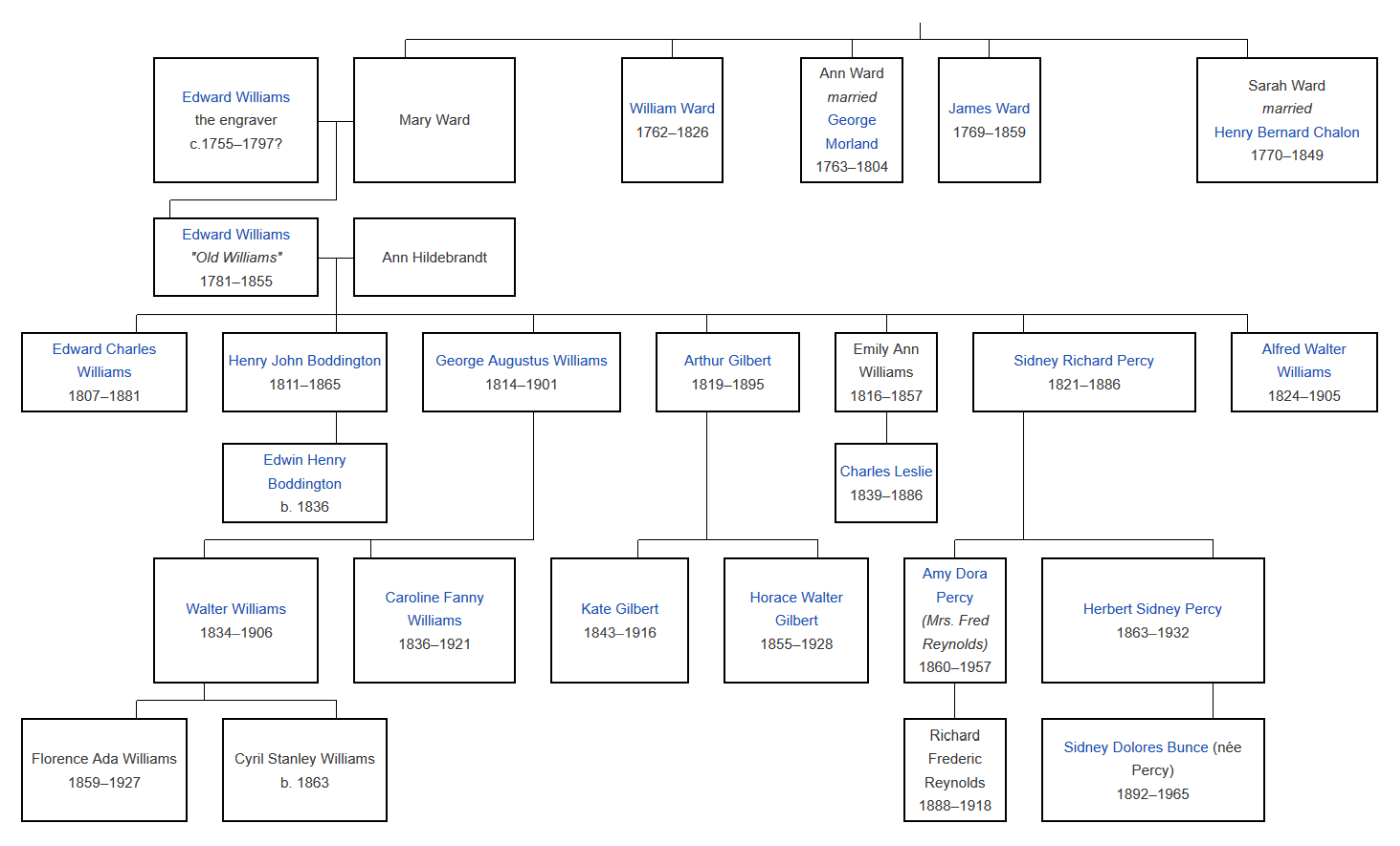

click on the blue links more information

click on the highlighted names for more information

|

| ||||||||||||

GlossaryAlbumen Paper Prints in the late 1850s began to replace salt prints as the most popular process for creating positive paper prints from photographic negatives. The process is so named because it uses albumen from egg whites to bind the light-sensitive photographic chemicals to the print paper. The image then emerges when the paper is exposed to light, whereas the image on a salt print does not require exposure and emerges when the salt paper is placed in a developing solution. Although salt prints could handled and displayed as is in photo albums, albumen paper prints were extremely thin, and almost always are placed on a carboard backing to prevent the paper from curling, cracking, and/or tearing. Ambrotypes, or collodion positives as they were known in Britain, are photographic images created on a sheet of glass coated with a silver-based, light-sensitive photo-chemical known as collodion. The process was patented in 1854, about 15 years after the appearance the more famous daguerreotype, which is an image produced on a mirror-polished surface of silver coated with silver halide crystals. Because ambrotypes are much less expensive than daguerrotypes to produce, they largely replaced the former in popularity by the late 1850s, before being replaced in the mid-1860s by the tintype and other processes. An ambrotype begins as a clean glass plate, one side of which is covered with a thin layer of collodion - a light-sensitive solution of nitrocellulose dissolved in ether and alchohol, sometimes acetone and alcohol, that dries to a celluloid-like film. The coated plate is dipped in a silver nitrate solution and, while still wet, is exposed to the subject for five to sixty seconds, depending on the available light. The wet plate is then developed and fixed. The resulting negative, when viewed by reflected light against a black background, appears positive, with the thickness of the glass adding a sense of depth. Usually a black varnish is applied to the back of the glass to provide a dark background, and another plate of glass cemented with a clear resin over the fragile emulsion side to protect it. The whole is then mounted in a metal frame and kept in a protective case. Ambrotypes were often hand-tinted, as untinted ones tended to be grayish-white, with less contrast and brilliance than daguerreotypes. Art Exhibitions were very popular in Victorian England, as this was a time when painting, especially landscape painting, reached new levels of awareness and appreciation. The were many Victorian exhibitions, but three stand out at as the most prestigious of these times. They were the annual Summer Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Art at Burlington House, the annual exhibition of the Royal Society of British Artists at its gallery on Suffolk Street, and the exhibitions of the British Institution and the National Institution. The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) was founded in 1768 by a group of artists who broke away from the Society of Artists (founded in 1860) after a leadership dispute. The Academy, which is housed in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London, does not receive support from the state or crown, but generates a large part of its income from hosting public art exhibitions. The prestigous Summer Exhibition, held in July and August in Burlington House most years since 1769, is the best-known of these. It is also the largest, and most popular open art exhibition in the United Kingdom. Although anyone may exhibit at the Academy, actual membership is limited to 80 elected artists (designated R.A.) who must be "professionally active in Britain". The Academy rules also stipulate that at least 34 of these members must be sculptors, architects and printmakers, with painters making up the balance. A larger number of Associates (designated A.R.A.) are also elected. The Academy also runs a postgraduate art school, and the Royal Academy Schools are the oldest in the country. Two exhibitions are generally held each year to display work by Academy students. The Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) was established in 1823 by a small group of painters who broke away from the Royal Academy. The RBA has 110 elected members who participate in an annual exhibition that was held at the the Society's Suffolk Street Gallery from 1824 until being relocated in the 20th century to the Mall Galleries of the Federation of British Artists. Queen Victoria granted the Society a Royal Charter in 1887. The British Institution was founded by Sir Joshua Reynolds and some fellow artists in the Royal Academy in London in 1805 as a private organization following some displeasure with the facilities at the Academy. Membership was limited to art patrons, unlike the Academy, which admitted only practicing artists. The British Institution in 1867 disbanded. The National Institution, not to be confused with the British Institution, began as the "Institution for the Free Exhibition of Modern Art" in 1847, in a temporary pavillion in the Hyde Park Corner of London, and later in the nearby Chinese Gallery. It was not really free, as it charged admission, and artists had to rent their display spaces and pay the exhibition a sales commission. However, spaces were assigned by lottery, and artists were free to show what they wanted the way they wanted, which was in marked contrast to how exhibitions were handled elsewhere. The "Free Exhibition" became the "National Institution of the Fine Arts" and moved in 1850 to the Portland Gallery on Regent Street, where it died out after 1861, or so. Mezzotint Engravings are made using tiny dots to generate different tones in paper prints, and it was the first process by which half-tones could be created without using hatching, cross-hatching or stipple. The actual engraving is made using a printing plate with thousands of tiny depressions, or pits, on the face of the plate that hold ink when the face is wiped clean. When the face of the plate is pressed onto the paper, the depth of the pits determines how much ink makes it onto the paper, with more ink resulting in darker tones. The printing plate is prepared using a curved metal tool called a "rocker that has tiny metal teeth on it to press into the face of the plate and roughen it to create the pits. The mezzotint process first appeared in the mid-1600s, but it was from about 1750 to 1820 that the collecting of mezzotint prints was probably at its greatest popularity. Salt Paper Prints were the first, and from about 1839 to 1860 were the most popular, process for creating positive paper prints from photographic negatives. The process is so named because it uses paper coated with light-sensitive silver salts to produce positive prints from both glass and paper negatives. However, the paper negative, which is called a calotype, was far more widely used. Although salt prints offered ease and flexibility, daguerreotypes (images on tin) and ambrotypes (images on glass) remained popular, as they were sharper, more clear, and more detailed, than prints from calotype negatives that by comparison appear grainy and fuzzy. The salt paper print process decreased in popularity rapidly after the 1850s when albumen prints appeared. |